I’m sure there is an alternative universe in which my wife is an artist. A fashion designer, or a painter, or at the very least an architect instead of a civil engineer. But her parents “suggested” her to study something that would get her a “proper” job. More specifically, they probably said “Child, you go and become an engineer”, to which she responded “Okay, daddy”. So, creative DIY projects became her hobby rather than her career.

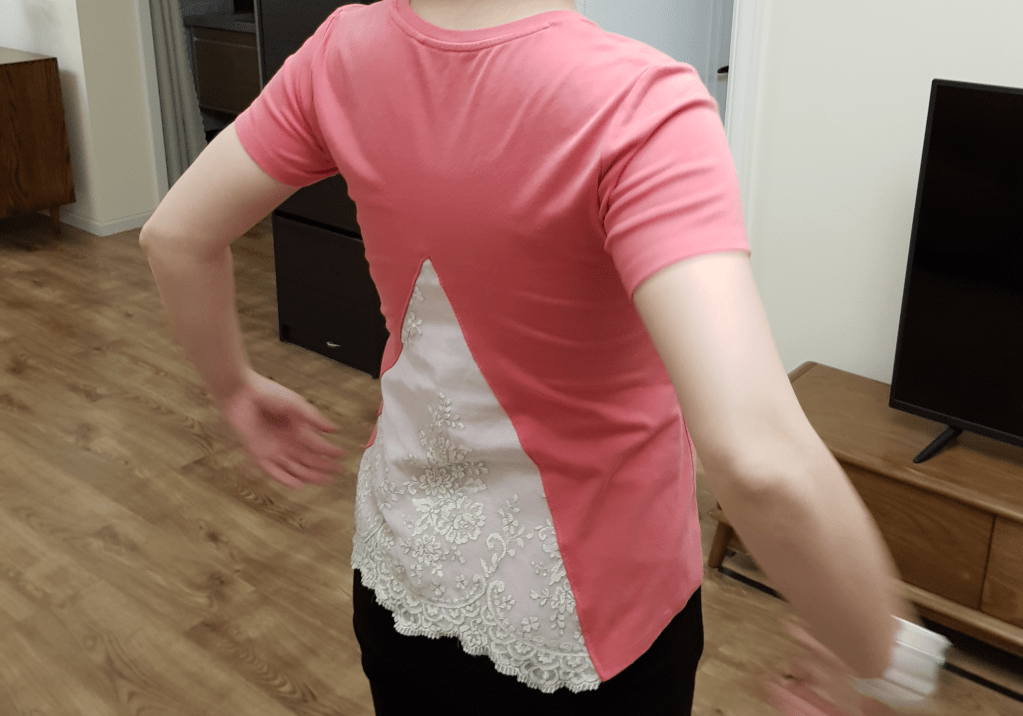

One of her projects combined her passion with a beautiful necessity: her bump had been growing for a while and we were expecting our first child. Soon her clothes didn’t fit anymore. So she started sowing together multiple old t-shirts to turn into new pregnancy-sized t-shirts. She carefully selected fabrics and colours to turn them into pieces that proudly showed the message: “I’m pregnant and it’s beautiful”.

One-hundred family blanket

During those months, I became familiar with the various traditions, habits and rituals that surround pregnancy and child-birth in China. One of them is another handicraft project: the Bǎijiābèi 百家被, roughly meaning one-hundred families blanket. It consists of 100 pieces of fabric sewn together to a blanket. These one hundred pieces were originally meant to be donated by one hundred different households, each sending it with their best wishes for the child, but nowadays, you can just order packs of 100 pieces from Taobao (which is what Ali Express is called in China).

The world would be such a simple place if these kinds of traditions were all there was to intercultural differences.

Yuèzi 月子 – Confinement

But it’s not. The most challenging Chinese tradition surrounding pregnancy and child-birth for intercultural couples is the Yuèzi 月子 – the “month of confinement”. In fact, I once read a research paper that found that in Chinese-Western couples, the Yuèzi 月子 ranks among the four most common sources of conflict, next to the subsequent child-rearing, money, and the in-laws (admittedly, the in-laws are probably a source of conflict everywhere in the world, no matter how nice they may be).

The Yuèzi 月子 is the tradition that the mother should stay at home for one month after giving birth in order to recover. Nothing wrong about that, in fact, it’s probably la good idea, in principle at least. The problem is that the Chinese just take it way too far.

Big disclaimer here again, that this is just my own very biased subjective impression, if you are looking for factual unbiased information about the Yuèzi 月子 then this blog is not for you.

In the most traditional sense, the young mother is not even allowed to leave her bad (except for going to the toilet, I would guess). She is not allowed to wash her hair, because she could get a cold if she did. She also can’t open the window, for fear of getting a cold. And the air-con is an absolute no-no. Keep in mind that it’s 40°C in Beijing in summer, though! She is not allowed to brush her teeth either – I forgot the reasoning behind this, but I remember that many dentist were said to be horrified after meeting young mothers for the first time again.

Needless to say that nowadays, most women don’t follow the rules all that strictly. Luckily.

However, there are rules that are followed by virtually everyone. The saddest one is that mothers are not allowed to lift up their own baby. They can lie the baby next to them, of course, but they can’t lift them or hold them up on their chest or belly. I guess the idea is that the mother is not going to overexert herself or put unnecessary strain on her womb. Now this gives rise to a problem: how are you gonna get the baby out of its crib into the mother’s bed for feeding? How are you gonna change the nappies? The answer is that you need a third person. Not the father of course, because men are well-known for being completely useless at taking care of a baby (a view that I tried my very best to challenge in China). There are only two options: mom-in-law or a professional nanny that is specially educated in the Yuèzi 月子, which are called Yuèsǎo 月嫂. These are middle-aged ladies that move in with young families for a month to raise the child and take care of the young mother.

I was horrified at the prospect of having a complete stranger living in our house right at the time when I and my wife wanted to bond with our baby and learn how to be parents. So I settled for the lesser evil of having my mom-in-law move in (traditionally, it should have been my mom, but alas, my mom is German and has other things to do than cooking food for my wife and changing the nappies of my child).

Cultural misunderstandings

There are a hundred blog posts that could be written just about this one month. But I’ll keep those for another day and talk about the “grammar and tones“, intercultural understandings and misunderstandings that led to this arrangement.

Here is the way the conversation should have gone:

Wife: Beloved dear husband, I’m pregnant, and Yuèsǎo to live with us for a month after the birth.

Me: That sounds like a horrible idea!

Wife: But it’s really important to me, in my culture this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience that I don’t want to miss.

Me: Alright then.

But this is not how it went. Remember we speak the same language while not really speaking the same language. Both of us speak English to each other. But both of us speak it with our unique cultural background shaping the words we say and the way we understand what the other one is saying. In the end both of us think we know what the other one is saying, when in fact we have no clue.

The conversation went more like this: My wife one day told me that she had made some pregnant friends, and one of them asked where to find a good Yuèsǎo. I asked what a Yuèsǎo and my wife explained my that she would cook food for her and change the kids nappies, and she would move in with them and charge about twice the median Chinese salary. So I mentioned what an absurd idea that was and why her lazy husband wouldn’t support his wife. After all I was cooking for my wife every other day and I was looking forward to take care of my baby. My wife mentioned that some Yuèsǎos wouldn’t allow the young mother to switch on the aircon, but that she thought that this was way to extreme and that if we directed the airflow away from the bed, it would be ok to use it in scorching Beijing heat.

Another day my wife told me that her friend said that her husband would just hang out in his underwear and play with his phone all day instead of supporting her, to which I responded that he most be a real looser type of guy. My wife said that this was the reason you needed a Yuèsǎo, but also confirmed that I was a wonderful husband and soon-to-be-father who would certainly take good care of the baby.

Yet another day, my wife told me that she had now made a lot of pregnant friends and all of them are discussing where to find a good Yuèsǎo. I asked if it had occurred to any of them at all to actually take care of their own child themselves, together with the fathers, to which my wife responded that they themselves would be so weak that they couldn’t and their husbands were so useless that they wouldn’t. She also said that they thought it would be even better if a maid moved in to cook and clean, in addition to the Yuèsǎo, who could then solely focus on the young mother’s and baby’s need. And of course, the parents-in-law should move in “to help” the young family (till today I don’t quite understand what this “help” means). My wife said that this meant that there were 7 people living in a two-bed apartment: the young mother in one bedroom to recover, the baby and the Yuèsǎo in the other bedroom, the maid in the kitchen, and the husband and in-laws on couch and air-mattresses in the living room. My wife thought that this was a bit crazy, and I thought that this was utterly crazy. A family for me is: mum, dad, child.

The conversation went on like this.

The thing is, while there were some aspects that my wife found just as absurd as I, there were others, such as the general idea of having a Yuèsǎo move in, that she was very much looking forward to. The more of these stories she told me, however, the more grotesque the very concept of a Yuèsǎo seemed to me.

One thing I didn’t understand well enough at the time is that in the Chinese culture, people generally want what others have. They think that what others think is right, is right. They don’t distinguish very much between: this is what you think, and that is what I think; this is what you want, and that is what I want. Instead, the reasoning is much more: everyone says this, so that’s gonna be right; everyone wants that, so that’s what I want.

In Western culture, and especially German culture, which is known to be very straight-forward, if I say that my friend hired a Yuèsǎo, it’s got nothing to do with me whatsoever. In Chinese, if I say that my friend hired a Yuèsǎo, the wish that I want one, too, is implicit.

By the time we had to make a decision, I was already completely convinced that a Yuèsǎo in my house would just show what a lazy phone-playing couch-potato husband and dad I was, and the Yuèsǎo would just grab the baby out of my hands from any moment I would get close to him (in fact, that’s what my mum-in-law still tends to do when she is around, although both of us are getting much better at understanding each other). My wife, on the other hand was already complete convinced that Germans must just have a Yuèsǎo-aversion-gene and the poor Chinese wives married to a German simply had to accept this as one of the various intercultural complications that arise in mixed couples.

We settled for mom-in-law moving in for a while as a compromise, but in hindsight, I should have erred much more on her side, if I had only understood the cultural context and the cultural way of expressing things better. Sorry, wifey.

Leave a comment